Welcome at the Interface Culture program website.

Acting as creative artists and researchers, students learn how to advance the state of the art of current interface technologies and applications. Through interdisciplinary research and team work, they also develop new aspects of interface design including its cultural and social applications. The themes elaborated under the Master's programme in relation to interactive technologies include Interactive Environments, Interactive Art, Ubiquitous Computing, game design, VR and MR environments, Sound Art, Media Art, Web-Art, Software Art, HCI research and interaction design.

The Interface Culture program at the Linz University of Arts Department of Media was founded in 2004 by Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau. The program teaches students of human-machine interaction to develop innovative interfaces that harness new interface technologies at the confluence of art, research, application and design, and to investigate the cultural and social possibilities of implementing them.

The term "interface" is omnipresent nowadays. Basically, it describes an intersection or linkage between different computer systems that makes use of hardware components and software programs to enable the exchange and transmission of digital information via communications protocols.

However, an interface also describes the hook-up between human and machine, whereby the human qua user undertakes interaction as a means of operating and influencing the software and hardware components of a digital system. An interface thus enables human beings to communicate with digital technologies as well as to generate, receive and exchange data. Examples of interfaces in very widespread use are the mouse-keyboard interface and graphical user interfaces (i.e. desktop metaphors). In recent years, though, we have witnessed rapid developments in the direction of more intuitive and more seamless interface designs; the fields of research that have emerged include ubiquitous computing, intelligent environments, tangible user interfaces, auditory interfaces, VR-based and MR-based interaction, multi-modal interaction (camera-based interaction, voice-driven interaction, gesture-based interaction), robotic interfaces, natural interfaces and artistic and metaphoric interfaces.

Artists in the field of interactive art have been conducting research on human-machine interaction for a number of years now. By means of artistic, intuitive, conceptual, social and critical forms of interaction design, they have shown how digital processes can become essential elements of the artistic process.

Ars Electronica and in particular the Prix Ars Electronica's Interactive Art category launched in 1991 has had a powerful impact on this dialog and played an active role in promoting ongoing development in this field of research.

The Interface Cultures program is based upon this know-how. It is an artistic-scientific course of study to give budding media artists and media theoreticians solid training in creative and innovative interface design. Artistic design in these areas includes interactive art, netart, software art, robotic art, soundart, noiseart, games & storytelling and mobile art, as well as new hybrid fields like genetic art, bioart, spaceart and nanoart.

It is precisely this combination of technical know-how, interdisciplinary research and a creative artistic-scientific approach to a task that makes it possible to develop new, creative interfaces that engender progressive and innovative artistic-creative applications for media art, media design, media research and communication.

ZEIT Campus

Ausgabe: N° 2/24

Das Magazin widmet der Studienrichtung Fashion & Technology zehn Seiten und präsentiert innovative Ansätze der Stofferzeugung in der Zukunft der Mode.

Textauszug:

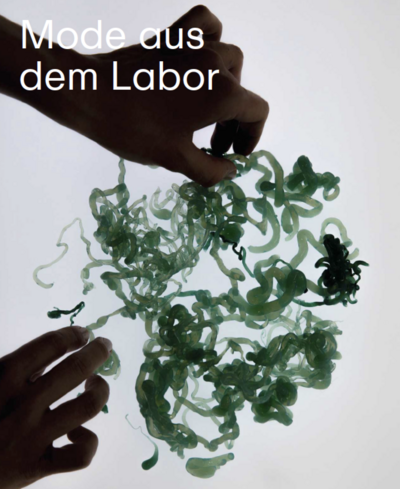

Im fünften Stock einer ehemaligen Tabakfabrik arbeiten Studierende zwischen Messbechern und Mixern an der Zukunft der Mode. Es sieht nicht aus wie in einem Hörsaal, sondern eher wie in einer modernen Großküche: Auf Edelstahltischen stehen Kochtöpfe, Waagen und Petrischalen. Hier wird an sogenannten bio materials geforscht, also Stoffen, die aus natürlichen Zutaten wie Algen erzeugt werden.

Durch die Fenster blickt man auf rauchende Schornsteine und graue Industriebauten bis zum Horizont. In der Nachkriegszeit taufte man Linz die Stahlstadt. Das Bild verändert sich. Seit 2014 ist Linz City of Media Arts, eine Auszeichnung der Unesco für zukunftsorientierte Städte. Die Kunst-Uni Linz bietet hier seitdem einen Studiengang an, der in Europa nahezu einmalig ist: Fashion and Technology. Das Bachelor- und Masterprogramm verbindet Modedesign mit Techniken aus der Biochemie, 3-D-Simulation, Robotik und künstlicher Intelligenz. Was nach Science-Fiction klingt, ist für die etwa achtzig Studierenden greifbar.

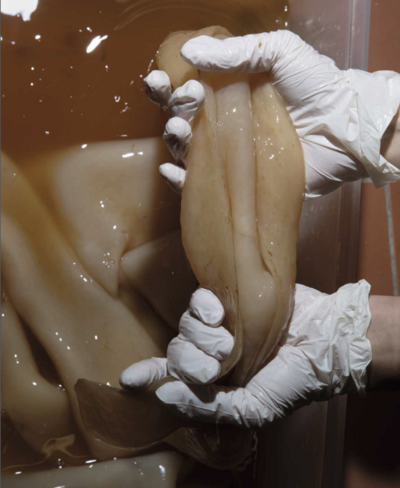

Eine von ihnen ist Sandra Axinte, 32. An einem Dienstag im Dezember streift sie sich weiße Einmalhandschuhe über und öffnet den Reißverschluss der Plane eines Brutschranks. Ein sßuerlicher Geruch durchdringt den Raum. Sandra holt ein Glas heraus und hät es ins Licht. Ein heller Klops schwimmt in einer trüben Flüssigkeit. Das ist die Ur-Mutter, ein Kombucha-Pilz, sagt sie. Den habe ich von einem Freund bekommen, der daraus das Getränk herstellt. Sie züchtet damit pflanzliches Leder.

Ihr Pilz ist eigentlich kein Pilz, sondern ein kleines Ökosystem aus Hefe, Bakterien und Cellulose. Im Grunde ist das wie ein fermentierter Tee, sagt Sandra. Ihr Kombucha-Pilz vermehrt sich laufend: Sie schneidet ein Stück davon ab, füttert ihn in einer Wanne mit Tee und Zucker und wartet, dass er in die neue Form wächst. Sandra zeigt auf eine Holzplatte: Das Stück habe ich gerade geerntet. Die dicke Scheibe erinnert an rohes Fleisch: sabschig und weich. Sie hat es mit Wasser und Handseife abgewaschen. Wenn es getrocknet ist, wird sie es mit Bienenwachs oder Öl bestreichen und kann dann Kleidung daraus nähen oder zusammenkleben. Für ihre Bachelorarbeit mit dem Titel Culinary Turn entstand so zum Beispiel eine Weste. Ich stelle mir vor, dass wir alle irgendwann Kleidung in der Küche kochen, sagt Sandra. In der Mode könnte der Kombucha-Pilz, der aus Ostasien stammen soll, eine Revolution sein, er könnte Leder ersetzen. Denn den Pilz kann man einfach züchten und im Gegensatz zu Tierhäuten CO₂-arm erzeugen sowie ohne giftige Chemikalien weiterverarbeiten. Konventionelle Materialien wie Tierleder sind umweltschädlich, sagt Sandra. Ich habe trotz meiner beschränkten Mittel gemerkt: Es wäre so leicht, das zu ändern.

weiterlesen: ZEIT Campus.pdf